The year 1946, extending into the early months of 1947, was a period of intense negotiation for Bulgaria as it sought to define its post-war status through the Paris Peace Treaty. These negotiations were critical in determining Bulgaria’s place in the post-war international order and its relations with the Allied powers.

In the subsequent 4-5 years, Bulgaria, including its capital Sofia, underwent significant reconstruction efforts. However, these efforts were heavily influenced by the Soviet model and directives, reflecting the geopolitical realignment of Eastern Europe under Soviet influence after the war. This transition to a Soviet-style governance and economic system marked a profound shift in Bulgaria’s political and social landscape.

The adoption of the Soviet model led to a centralization of power and a suppression of state, municipal, and private initiatives. This period saw the nationalization of industries and the collectivization of agriculture, alongside a clampdown on political dissent and a restructuring of societal institutions to align with socialist principles. The impact of these changes was far-reaching, affecting the fabric of Bulgarian society and its capital’s development. Sofia, as the capital, became a focal point for the implementation of these policies, significantly shaping its post-war recovery, urban development, and political identity.

In 1945, amidst the transformative post-war period, Sofia adopted a new general urban planning plan, known as the Neikov plan. This plan laid the groundwork for the capital’s development in the coming years, shaping its expansion and modernization efforts.

The political landscape of Bulgaria underwent a significant change after a referendum in 1946, leading to the proclamation of a people’s republic and the establishment of a patriotic front government. This transition marked a pivotal shift in the country’s governance and had a profound impact on the capital’s development. Sofia’s population began to surge, largely driven by policies of centralization and collectivization that encouraged migration from rural areas to the capital. The emphasis on heavy industry and industrialization became more pronounced, influencing urban planning and housing construction activities within the city.

The commissioning of the “Kremikovtsi” plant in 1958 exemplified the push towards industrial development. Efforts were also made to expand and modernize the road network and urban transport systems, catering to the growing needs of the capital’s increasing population.

However, the 1970s witnessed a significant pushback from architects against earlier plans to overhaul the city center for new socialist construction, which would have entailed the demolition of many old buildings to make way for modern structures. This resistance led to the preservation of several key historic and cultural sites within Sofia. Notable examples include the former royal palace, the Military Club, the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (BAS), and other buildings near the Central Halls, the Women’s Market, and along Pirotska and Exarch Yosif streets. The preservation of these sites amidst the drive for socialist modernization reflects a nuanced approach to urban development, balancing the city’s rich historical heritage with the demands of contemporary growth and change.

During the communist regime, Sofia underwent significant changes not just in its physical landscape but also in the cultural and ideological representation of its public spaces. Many of the city’s iconic streets and squares were renamed to reflect the ideological stance of the government, aligning with the socialist and communist values that dominated Bulgaria during this period. However, following the fall of communism in 1989, a movement to restore the historical and cultural heritage of Sofia led to the reinstatement of most of the previous names, reestablishing a connection with the city’s past and its historical identity.

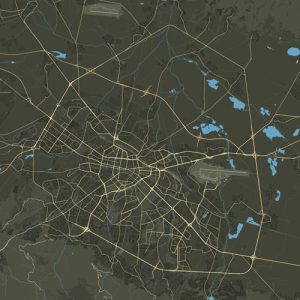

In the second half of the 20th century, Sofia’s administrative boundaries expanded to include many neighboring villages that were previously independent. This expansion was part of a broader strategy to manage the city’s rapid population growth and to integrate surrounding communities into the urban fabric of the capital. Notable incorporations include Birimirtsi and Obradovtsi in 1955; Knyazhevo in 1958; and a significant addition in 1961 of Boyana, Vrazhdebna, Vrabnitsa, Gorna Banya, Dragalevtsi, Darvenitsa, Iliantsi, Malashevtsi, Obelya, Orlandovtsi, Simeonovo, and Slatina. This trend continued in the 1970s, with Suhodol, Trebich, and Filipovtsi joining in 1971; and Botunets, Gorubliane, Kremikovtsi, Seslavtsi, and Chelopechene in 1978.

These expansions reflected the growing needs of Sofia as a major urban center, aiming to provide adequate housing, services, and infrastructure to a growing population. The integration of these villages into the city’s structure was a significant step in the development of modern Sofia, shaping its contemporary layout and dynamics.

The development of Sofia’s road network, including its ring or district roads, boulevards, and streets, has been integral to its growth and urban planning since the city’s initial construction phases. The boulevards Slivnitsa, Ferdinand (known today as Vasil Levski), Patriarch Evtimiy, and Hristo Botev were among the foundational thoroughfares in the early periods. Additionally, the northern part of Princess Maria-Louisa, General Nikolay Stoletov, Danail Nikolaev in the northeast, Evlogi and Hristo Georgievi in the east and southeast, Pencho Slaveikov in the south, and Ing. Ivan Ivanov and Konstantin Velichkov in the west, were pivotal in establishing the city’s initial layout. Many of these boulevards, like Okrzhen Blvd., were named during this time, embodying the city’s evolving identity and infrastructure needs.

These boulevards now largely demarcate the boundaries of today’s city center, forming a historic core within the modern urban landscape of Sofia. In the latter half of the 20th century, additional boulevards such as Vardar, Gotse Delchev, Nikola Vaptsarov, and Peyo Yavorov emerged as significant arteries, further enhancing the city’s connectivity and accessibility. These newer boulevards acted as contemporary counterparts to the original thoroughfares, playing crucial roles in the city’s ongoing expansion and in accommodating the increasing demands of traffic and urban development.

This network of boulevards and roads has not only facilitated movement within the city but also reflected Sofia’s growth from a historical capital to a dynamic, modern metropolis. The evolution of its road infrastructure is a testament to the city’s adaptability and its planners’ foresight in meeting the challenges of urbanization and modernity.